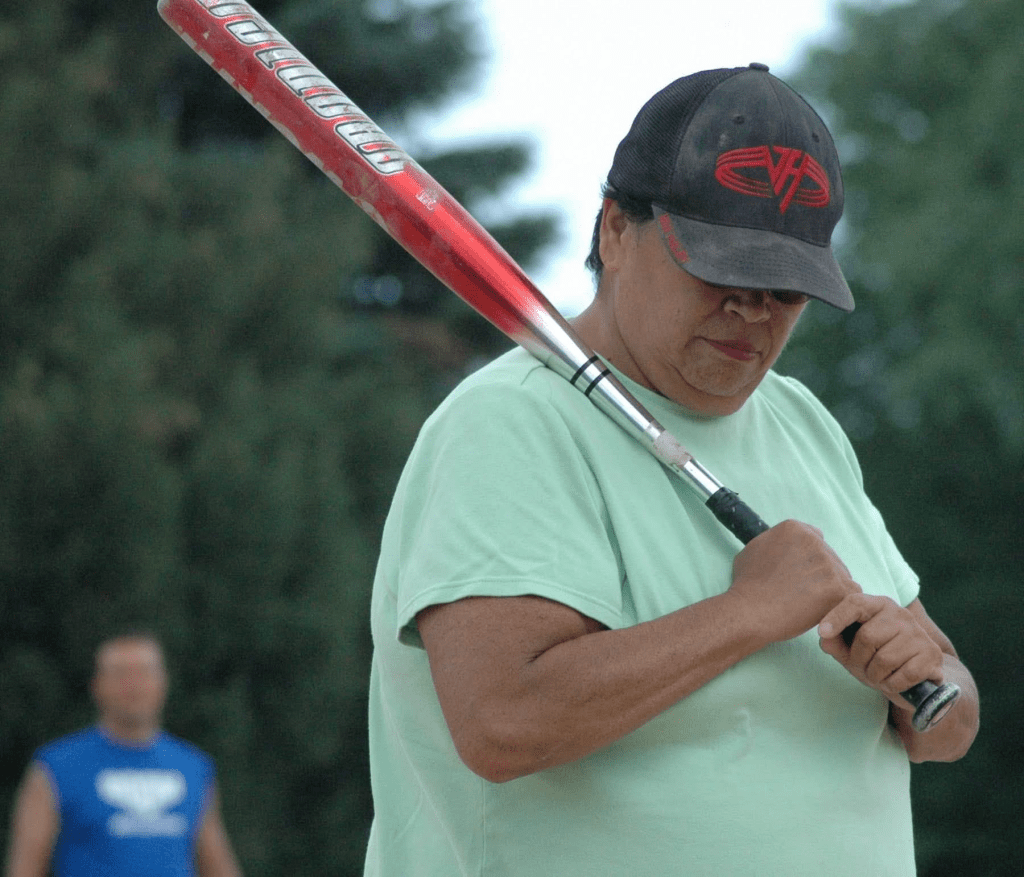

Getting to Know...Mona Garcia

There are allies to our community, and then there is Milwaukee’s Best, Mona Garcia.

The 74-year-old straight woman of Mexican ancestry may seem like an unlikely person to be one of the staunchest allies of the queer softball movement, but when you know her history, it’s hard to imagine her being anything else.

That’s because she’s no stranger to being judged and excluded simply because of who she is.

“I grew up in the 1950s and I remembered our neighbors were boycotting the local bank. The bank was going to give a loan to my parents so they could buy a house,” Garcia said. “The neighbors didn’t want Mexicans in their neighborhood.”

But Redlining wasn’t where the discrimination stopped for her family.

“We couldn’t go to certain restaurants. We weren’t allowed to use the public pools or even the bathrooms,” she said. “I lived through that. I experienced that.”

Fast forward 50 years and Garcia would find herself a single parent to her son and working at Northwestern Mutual. Like many women of a certain age, Garcia’s favorite co-workers were her gaggle of gay friends. She didn’t know much about them or the worlds they experienced, but as she built trust with them, they came to confide in her.

Garcia said that one day one of her friends was having a particularly rough time. “He confided in me that he wished people could see past him as a stereotype and just see him as a person. He said that he felt really hurt.”

In that moment, a light would switch on in Garcia that would forever change her life, and shortly thereafter, the queer softball movement.

“I knew then and there that I needed to spend my life helping people feel okay about who they are,” she said. “I may have grown up with a very different kind of rejection, but the hurt was the same. I didn’t want anyone around me to ever feel that way.”

Garcia got to know her friends at work on a deeper level. She would socialize with them after work.

“We’d go to these bars and they would just be totally different people,” Garcia said. “They didn’t have to pretend.”

One of the people Garcia met through her coworkers was Mark Upham, who managed and played softball in the Saturday Softball Beer League (SSBL). He and Garcia became great friends and Garcia started going to the games as an athletic supporter.

“I wasn’t going to the bars or the fundraisers at that point,” she said. “I would just go to the games and then go home. But the more I would go, the more I would get involved with other players on the team and before long I would go with the team after their games to their home bar, which was called The Ballgame.”

Upham passed away suddenly in 2001 from a heart issue and, understandably, Garcia was devastated. In addition to mourning the loss of her friend, she also realized she missed the camaraderie of the softball family she’d been adopted into. But she stayed away.

That didn’t work for the rest of the team, as it turns out.

“A few weeks after Mark’s death, some of the team members reached out to me and said they missed me, that it wasn’t the same without me,” Garcia said. “So they came and got me and I started going to the games again.”

But not everyone was excited to see Garcia around so much. “I had to build trust with people,” she said. “Gay men would sometimes come up to me and ask me ‘Why are you here?’ My answer was simple. ‘I’m here to be with friends. Why are you here?’”

This trust was solidified one Saturday after the league’s games were all wrapped up for the week and the team ventured out to the bar where the league’s event was that weekend. Garcia went in with the team, but the owner of the bar wasn’t happy to see her.

“He didn’t want to sell to me,” she said. “Some of the players said ‘Well, just sell it to me, then.’ But the owner didn’t want women in his bar and he said I had to leave.

The players didn’t like that so they said if I go, they go. And they did. They all left with me.”

At that moment Garcia knew that this community she’d been supporting was going to always support her right back.

But it was another league event, at a different bar, that would change the course of Garcia’s life yet again.

“We were at this fundraiser and there was this guy running around. He just had this attitude about him. He was telling everybody what to do and just seemed really unpleasant.”

Garcia asked one of the players who that guy was. They told her he was the league’s commissioner and he was just that way sometimes. “He was doing everything, trying to get everything done.”

Garcia said that as the night went on, someone convinced him to strip down to his skivvies and get soaked with a water-hose, and to auction the rights off to spray him down to the winning bidder.

“Well, there was no way I was going to lose that auction,” Garcia said. “Someone needed to cool him off.”

Garcia made sure to win the auction and she took aim with the sprayer. “I had two minutes to hose him down and I went from his mouth to his crotch, to his mouth, to his crotch!”

That Commissioner was NAGAAA Hall of Famer and longtime SSBL commissioner Brian Reinkober. The two would somehow become inseparable friends after that, with Reinkober getting the ultimate revenge not long after.

In 2003, Reinkober would strike. “I was at the SSBL Annual Banquet and had to go to the bathroom,” Garcia said. “When I got back they were all clapping. I asked what they were clapping for and Brian told me ‘they just elected you Treasurer!’ How? I wasn’t even here!”

Garcia would serve as SSBL Treasurer for 10 years, despite only ever playing in two actual games. She credits Reinkober with instilling in her a vocabulary for the game. “He really taught me how to talk about it and be intelligent about what I was saying.”

During her time as Treasurer, Garcia would attend the Winter and Summer meetings with Reinkober as a delegate alternate and would, on occasion, sit in the primary chair to voice her concerns or opinions on the issues.

Then in 2012 the national board was looking to add a staff position of Executive Assistant, but they didn’t know exactly how the position would look, what they would do, or how much they would pay that person.

“That didn’t make any sense to me,” Garcia said. “I explained that the council couldn’t vote for that kind of thing because they didn’t know what they’d be voting for.”

Eventually Garcia would volunteer to take the role for one year. “I could do the job, write the job description and from that they could get a sense of how much to pay that person.”

It seemed to be a sensible plan. She would help the board out for one year and then be done.

Garcia would serve in that volunteer capacity for seven years, seeing some of the national board of officers turn over, being the one constant to which each new administration could anchor as they charted a new course forward.

She was never paid, at least not with money.

“I loved getting to meet so many people in this organization, from all over,” she said. “Being in a position to be exposed to all that was such a great thing. Some of my proudest moments are when I’m in some random city now and someone says “Oh you’re Mona from Milwaukee!”

But her proudest moment was when former national commissioner Chris Balton announced the Mona Garcia Volunteer Award.

“I wasn’t the first volunteer and I sure won’t be the last, but I’m hoping that by putting my name on it means that other people will be inspired to do good work, too.”

It’s hard to know how many people who have participated in the queer softball movement across the country since International Pride Softball was founded almost 50 years ago. Currently there are about 18,000 participants.

Since its inception in 1997, only 238 people have been selected for the national Hall of Fame. It’s an even smaller percentage who have been selected their first time appearing on the ballot, and an even smaller percentage of people with Mexican heritage, and an even smaller percentage who are women. There’s only one person to be selected for the Hall of Fame who ticks all those boxes and who is an ally to the queer community.

That is Mona Garcia.